There is a paradoxical “question” used in justifying torture, a sort of devil’s advocacy. The question was originally put forward by a German politician in the 70s. It was brought up again recently in the Israeli High Court in a case regarding the removal of a legal provision which permitted ill-treatment and is as follows:

“A group of people have a bomb that could destroy a whole city and they will use it in 24 hours. You capture someone who knows the location of the bomb. You are forced to choose between either accepting the death of everyone in the city or getting this information using force despite knowing that this is not right.”

The Lesser Evil

These devil advocates offer two choices representing two contradicting values: On the one hand, there are the lives of thousands of people and, on the one hand, the damage that will be inflicted to the integrity of the body and mind of one person. The clash of values is reinforced by the proposition that it is not the life of one person but the lives of thousands of people which are at stake. Furthermore, the clear prior knowledge that is supposed to exist regarding the time frame and the involvement of the suspect are also used to push the one to whom this question is addressed into a corner. We are forced to watch a play on a stage where the spotlights shed light only on one spot and we are not allowed to see anything else.

Taner Akçam tries to come over this by saying “… it is not meaningful to discuss a moral principal through unlikely scenarios.”** I agree with him. Yet at the same time I think that this scenario comprises some very useful elements which can help us to understand the phenomenon of torture. Therefore, I am choosing to ignore the weaknesses in the question and to fall into the trap. Let us watch the play to the end…

The Play Begins

Let us assume that this really happened; we sincerely believe that the whole city will explode in 24 hours, all of our loved ones will get killed and the only way to stop the explosion is to ‘make the suspect talk’. Torture is such an inhumane act; would you wait for the explosion saying that you can not possibly inflict pain on anyone even if it is to save the lives of thousands of people? This is a fully ethical standpoint. However, we are talking about “the attitude of an ordinary person” in a situation unlikely to occur in real life.

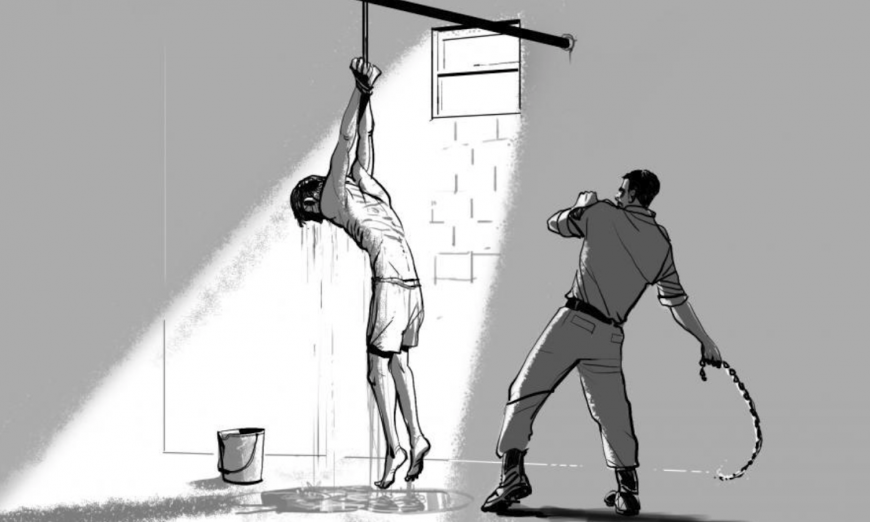

You respect human rights, you do not approve of torture, yet the lives of thousands of people are in danger… You decide to make an ‘exception’ (let us not forget that our lives are surrounded by many ‘exceptions’ that are against our values). First of all, you would probably try to persuade the suspect to give you the information. You might make threats like “Look, I do not want to hurt you. Just tell me where the bomb is or you will not be able to imagine what will happen to you”. The man is a ‘vicious terrorist’ and does not look like someone who would take notice of such threats. You blindfold him, you strip him naked and start to inflict psychological and physical pain: insults, beatings etc. He is still not talking… You need to increase the dose of pain. You give him bastinado , you start to apply electric shocks including to his penis, you spray him with cold pressurized water, you put a truncheon up his anus, you tie his hands behind him and hang him by his wrists etc… (these were, until very recently, the most commonly used methods of torture in Turkey according to the reports of international bodies). However, the man still does not talk. You have heard that there are some people who do not talk for months even under the worst kind of torture. Yet you only have 24 hours. You began to do unimaginable things; you start to cut bits of his body… In the end, you are ‘lucky’. The ‘terrorist’ finally starts to ‘talk’. The walls have echoed with screams and the room is covered with tears and blood, urine and excrement… but in the end you made him talk.

What next?

The bomb is found; thousands of people have been saved. The play is over, the lights are out, the curtain has fallen over the stage. You are now alone with your own conscience. Should you view yourself as a hero and feel proud, or as an accursed person who sold his soul to save people’s lives? Will you be irritated by the joyful people celebrating on the streets whose lives you saved because of the humiliation you went through on their behalf? Do you become even more tense knowing that they sleep well in their warm beds while you are drenched with sweat at the nightmares that appear before you? What about the society; the people you saved? How should they view you? A hero? A revered person who achieved an epic success? Or as someone who has undergone physical and mental abuse in order to save them, as someone whose place nobody would want to be in?

The Face of the Victim

American war movies ask us to make a choice between the two warring sides. While all the emotions of the good guys are captured through the use of camera angles and perspective, ‘the enemy’ is made to appear very cruel or like a silhouette without soul. The enemy is always ‘the other’ – he is not like us. Torturer blindfolds the victim. This is, like stripping naked, a way of destroying the victim’s sense of self, a way of causing anxiety. However, more than this, it is a way of turning the victim into an object, of turning him into the ‘the other’ by covering his face.

The teller of the above story presents the ‘terrorist’ as a murderer meaning to kill all people in the city. He also covers his face and his features and alienates him from us. Alienation is a precondition of torture.

Black Hole

Those who want to corner us with such ‘clever’ rhetoric do not, in fact, want us to think about anything else. The only issue they want us to examine is an analysis of profit against loss. In the case in the Israeli High Court that I mentioned in the beginning of my article, those who supported the legal provision which allows for “physical and psychological pressure and violence to be used during interrogation” also hid behind this kind of rhetoric.

They tried to use an example which is unlikely to occur in real life in order to justify the widespread and systematic ill-treatment of Palestinian convicts. The devil’s advocates were well aware that if the ban on torture is broken through in one area then the debate would move to another level and they would soon be able to include other ‘exceptional circumstances’. The rhetoric of the time bomb also ignores the fact that torture is not only used to get confession but also to punish the victim and send a message to the society through the body of the victim. It hides from us the fact that torture can be used on political dissidents, members of ethnic minorities, homosexuals, women and children. In short, against everyone.. We have not experienced the ‘time bomb’ so far but there are complaints of torture and ill-treatment in over 150 countries. In 70 of those countries, torture is common and systematic. In over 80 countries, there have been deaths resulting from torture.*** The aim of these devil’s advocates here is to create a ‘black hole’ which will justify and allow for all kinds of torture. Once the black hole is there it will hungrily swallow everything before it.

Absolute Ban

Ever since the United Nations Universal Human Rights Declaration, torture has been banned absolutely in all of the supra national human rights documents. Inhuman treatment and insulting treatment and punishment are also banned. This ban is absolute; it can not be violated during war, state of emergency or for any other reason. This is an important indication that those who prepared such human rights documents aware of the black holes. Torture is condemned to such a degree that, ironically, it can exceed the right to live. Under international law there might be situations where people may receive death penalty; however, nobody may be tortured.

A moral question

The rhetoric I mentioned above is not only used in Israel or Germany. I observed it as my dear friend, the lawyer Murat Dinçer, talked with the police officers monitoring the Izmir Bar Associsation’s general assembly. I gathered from their conversation that the same ‘clever’ mentality is in use among the members of security forces in Turkey. The conversation between the police officer and Murat got heated and moved to the issue of torture. The officer gave the above example with confidence: “Terrorists are planning to blow up Izmir. You’ve captured one of them and you have 24 hours…” The police officer was expecting Murat to be surprised and confused by this. However, Murat answered him with an equally cunning question: “Ok, let us say the Greeks occupy Izmir and the commander of the occupying forces says to you that he will either spend one night with your wife or he will blow up Izmir. You are convinced that he means it and there is no other way of saving the people of Izmir. Would you let the commander have your wife?” The police officer hastily replied “No” and continued “I would not let him”. Murat replied “Well, I would not torture, and nobody could condemn me for it”.

The attitude towards torture is therefore a moral one. The stance of a police officer who carries out torture is one that has been chosen. For example, in the case of Turkey, a police officer who tortures is even beyond the morals of ‘Anatolian macho culture’ which tells you: “Do not kick down, do not have a fight with someone weaker than you.” The attitude of a doctor who ignores the marks of torture is morally controversial; just like the attitude of a prosecutor who does not open a case despite evidence and or like the attitude of a judge who those who complain about torture to him that “he has nothing to do with that issue”.

The only way to oppose such a decay is to oppose the torture of the torturer and the gang member and mass murderer (let’s imagine who we hate the most) as energetically as we oppose the torture of people we feel sympathy for and to present the society with such a moral examples.

This is a question of being able to recreate a new morality!

** Taner Akçam, “İşkenceyi Durdurun” (“Stop Torture”), Ayrıntı Publishers, 1991, p.109

*** Beating on the soles of the feet

**** Amnesty International, “Take A Step To Stamp Out Torture”, London,2000, p.2-3

Orhan Kemal Cengiz