Thomas Hammarberg

[20/10/08] There are more than 80 million persons with disabilities in Europe. Their rights are recognized in international human rights treaties, including the recent UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. However, these rights are still far from realized. Moving from rhetoric to concrete implementation has been slow. Such steps also require a change of attitude – from a charity approach to rights-based action.

For far too long policies concerning persons with disabilities have focused exclusively on institutional care, medical rehabilitation and welfare benefits. Such policies build on the premise that persons with disabilities are victims, rather than subjects able and entitled to be active citizens. The result has been that men, women and children with disabilities have had their civil, cultural, economic, political and social rights violated.

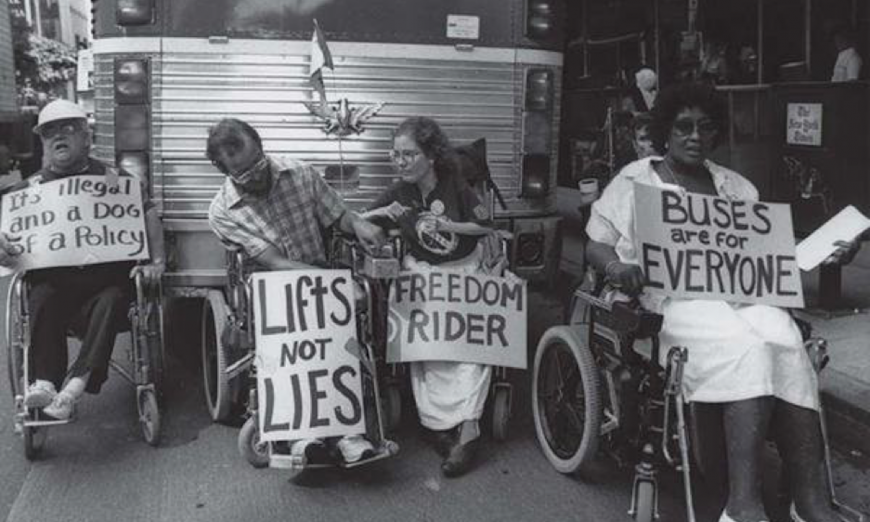

However, a gradual shift in thinking has started as a result of pressure from the disability movements and other civil society groups. They have played an important and active role in the development of the new UN Convention and the Council of Europe Disability Action Plan 2006-2015.

These two instruments confirm clearly that the rights of persons with disabilities are human rights. States have an obligation to respect, ensure and fulfill these rights. Participation of persons with disabilities in all decisions affecting their lives, both at the individual level and through their organisations, is recognised as a fundamental principle in both. Words like ‘inclusion’ and ‘empowerment’ are used in this context.

However, in real life persons with disabilities still face a number of barriers when seeking to participate in society. Children with physical disabilities cannot play with other children in public playgrounds because of their inaccessible design. TV programmes without subtitles exclude persons with hearing impairments.

Persons put under plenary guardianship are prevented from acting in almost all areas of life. They cannot, for example, vote, buy or sell things, or decide where to live, work, travel or marry.

Making societies inclusive requires planning and systematic work. It is therefore encouraging that several European states have now adopted disability plans and strategies. Every country will need to develop such plans tailored to its own circumstances. Those who have tried to set priorities, define time-limits and allocate budget resources and responsibility for implementation have generally been rewarded with positive results.

Such plans must address the situation of children with disabilities. Many of these children are still not accepted in ordinary schools because the schools are not equipped to meet their needs. The same thing happens at day-care centres, sometimes forcing parents to choose between leaving their children in institutional care or giving up their job in order to care for their child.

The situation of children without parental care is particularly serious. Life in an institution, separating children from their family and their social context, almost inevitably leads to exclusion. More resources are needed for supporting families, especially families living in poverty and single-parent households, to enable children to grow up in their family environment.

Childcare centres and schools should be open to all children and equipped to meet different needs. Social services and health care providers in the community must be accessible and competent to care for persons with different disabilities. Such reforms are challenging and require commitment and re-allocation of resources.

The right to education is equally important to all children. Even though every child’s ability to learn is undisputed, there are still children in Europe of school age who are considered to be “uneducable” and denied any form of education.

Such practices do not only limit the child’s options to support him or herself later as an adult, but also their possibility to become independent and participate in society. The obvious principle is that persons with disabilities have the right to receive quality education and no-one should be excluded from ordinary schools because of their disability.

Another group not to be forgotten in such action plans is aged people with disabilities. As a consequence of getting older many of us will develop for instance, reduced vision, reduced hearing or reduced mobility.

Innovative approaches are required to meet these challenges across a wide range of service areas. Co-ordinated action with the aim of enabling ageing people with disabilities to remain in their community to the greatest extent possible is essential. This requires an assessment of individual needs and forward planning as well as ensuring that the required services indeed are available.

Another aspect which must be taken up in the action plans is the situation of persons with mental disabilities. The situation in psychiatric institutions in several European countries is shockingly bad. I have seen institutions the conditions of which are so inhuman and degrading that they should be closed down.

Unfortunately, medication is too often used as the only form of treatment. There is an urgent need to apply alternatives, such as different forms of therapy, rehabilitation and other activities. Unclear admission and discharge procedures constitute another problem resulting in what in reality is arbitrary detention.

There are, however, also positive examples and trends to empower patients with mental disabilities by facilitating their active involvement in treatment plans and providing complaints procedures for those who feel that their rights have been violated.

As with all closed settings where the liberty of person(s) is restricted, effective complaints procedures as well as independent monitoring visits are of crucial importance. The Optional Protocol to the UN Convention against Torture requires states to establish national inspection systems to monitor all places of detention, including mental health and social care institutions.

Finally, persons with disabilities can also be victims of hate crimes and hate motivated incidents. Violence, harassment and negative stereotyping have a significant negative impact on disabled people’s sense of security and wellbeing and their ability to participate socially and economically in their communities. Research conducted by Mencap in the United Kingdom demonstrated that 90% of people with a learning disability had experienced bullying and harassment. In addition to general awareness-raising measures, proactive policing and prompt prosecutions are needed to tackle hate crime against persons with disabilities.

Full removal of social, legal and physical barriers to the inclusion of persons with disabilities will take time and require resources. But it has to be done. We cannot afford to keep barriers that prevent 80 million people from fully participating in and contributing to our societies as voters, politicians, employees, consumers, parents and taxpayers like everybody else.

Governments should now take action in order to realize fully the human rights of persons with disabilities:

• Ratify the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and the Optional Protocol and start implementing it. Use the European Action Plan as a tool to make the standards a reality.

• Develop action plans to remove physical, legal, social and other barriers that prevent persons with disabilities from participating in society. Consult with and include persons with disabilities and their organisations in the planning and monitoring of laws and policies which affect them.

• Adopt non-discrimination legislation covering all relevant areas of society.

• Set up independent Ombudsmen or other equality bodies to monitor that persons with disabilities can fully exercise their rights.

• Develop programmes to enable persons with disabilities to live in the community. Cease new admissions to social care institutions and allocate sufficient resources to provide adequate health care, rehabilitation and social services in the community instead.

• Review the laws and procedures for involuntary hospitalisation to secure that both law and practice comply with international human rights standards.

• Set up independent mechanisms equipped to make regular, unannounced and effective visits to social care homes and psychiatric hospitals in accordance with the Optional Protocol to the UN Convention against Torture.

• Tackle hate crime against persons with disabilities through proactive policing and prompt prosecutions.

This Viewpoint can be re-published in newspapers or on the internet without our prior consent, provided that the text is not modified and the original source is indicated in the following way: “Also available at the Commissioner’s website at www.commissioner.coe.int“