![]()

Strasbourg, 13 June 2007, CommDH/ Speech(2007)7, Original version

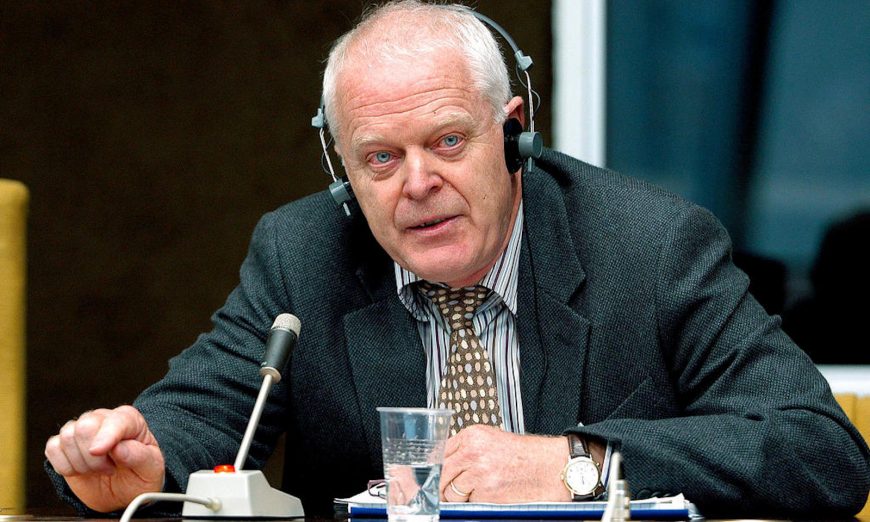

Keynote speech by Thomas Hammarberg, Commissioner for Human Rights, at the Council of Europe Conference: Democracy Forum, Stockholm, 13 June 2007

The individual has a right to take part in elections. The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights already defined participation in the government of one’s country as an individual right for everyone. It was specified that this right could be enjoyed “directly or through freely chosen representatives”.

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights stipulates that every citizen shall have the right and opportunities “(t)o vote and to be elected at genuine periodic elections which shall be by universal and equal suffrage and shall be held by secrete ballot, guaranteeing the free expression of the will of the electors”.

This right for the individual to take part in free, fair, universal and regular elections is the obvious bridge between the concepts of democracy and human rights. However, there are other obvious links.

I will argue that respect for all human rights is one of the necessary condition in which democracy flourish. I will also suggest that democracy is the best form of government for the protection of human rights.

The essence of democracy is of course about ‘rule by the people’, about who participates in the decision-making process and how. This is not only a question of certainin stitutions or procedures, there are key principles involved. I believe it is important to understand these principles and teach them in order to avoid that the term ‘democracy’ is diluted of its true meaning and turned into an empty slogan.

In a democratic society or association the decisions must be under the control of all its members and all of them should be considered as equal. Popular control and politicale quality are the two principles which build democracy.

This makes human rights norms – with their emphasis on governmental accountability and the rights of the individual – particularly relevant in the work for democratization. Popular control would in the human rights language relate to right to participation and the right to monitor those in power. Politicale quality relates to the principle of non-discrimination and genuine equality of opportunity to exercise one’s rights.

Some human rights are directly linked to the election procedures themselves such as the right to vote and the right to stand as a candidate. However, the formal elections would be a sham without what constitutes an open debate: freedoms of expression, association and assembly.

These freedoms are necessary in order for people to be able to monitor, criticise and influence – to exert popular control. Repression of peaceful dissent, even of the smallest minority, is an affrontand hurts democracy.

The respect for economic and social rights has also an impact on the efforts towards democracy. Political equality requires also that people are enabled to take part in the public decision-making – extreme poverty or lack of education are obvious obstacles, directly or indirectly.

In other words, there is an obvious interrelationship between democracy and human rights. Democracy will be stronger the more human rights are respected.

One area in which the human rights’ approach has added considerably to the democratic discourse relates to the limits of majority rule. A true democracy also entails protection of minorities and thereby a willingness to compromise to certain minority interests.

This is of course one of the classical democracy dilemmas. The truth is that many of the democracies in Europe still fail to listen to the minorities to the extent required by human rights norms and monitoring bodies. Xenophobia is a problem that our democracies find difficult to handle, especially during election periods.

In this area the human rights standards give guidance and protection. In fact, the underlying idea is that the agreed international and European human rights norms, when ratified, should stand above national and local politics. Even the broadest majorities should not be able to adopt policies which violate the rights of certain individuals in society. In that sense, human rights norms restrict the decision power of elected political assemblies.

The European Convention on Human Rights is already law of the land in all Council of Europe member States and has a constitutional status in some of them, for instance in Austria and Bosnia and Herzegovina. This prevents or blocs decisions which in advance have been defined as unwanted. Forinstance, it is practically impossible today for any parliament in Europe to reintroduce the death penalty – we Europeans have decided to protect ourselves against such an unfortunate decision in case, for instance, a sudden public opinion would demand such a move.

This is a refined form of democracy. In a democratic order we have decided to abstain from the consequences of total majority rule in order to secure a constant protection of human rights.

We have learnt from experience how crucial the principle of the Rule of Law is in the defence of human rights. Separation of power between the executive, legislative and judicial authorities is essential in order to avoid that too much power is concentrated in a few hands. I have seen with concern that some European governments interfere with the judiciary in political sensitive cases instead of respecting and encouraging a fully independent court system.

There are other aspects of “checks and balances” embedded in the human rights idea: that non-governmental organizations contributes also in their advocacy role; that independent ombudsmen and other national human rights institutions should be welcomed; and that the media must be free to criticize.

So far I have addressed you on the contribution of human rights to the democracy process. What about the reverse influence? Is democracy necessary for human rights?

Yes, it is notpossible to imagine a dictator as a human rights defender, he would be schizophrenic. It is not even true, as is sometimes argued, that non-democratic regimes can bemore effective in protecting economic and social rights. Amartya Sen and others have shown that authoritarian societies often lack capacity to detect and properly react on social problems.

This does not mean that there are no human rights problems in countries which we classify as democracies. The situation of the Council of Europe is illustrative. Though, it is a requirement for membership that the country is governed democratically, there are still problems relating to human rights in the Member States.

Some of them have not managed to uphold human rights principles in the combat against terrorism. They cooperated with an administration in Washington that practiced systematic torture, brought suspects to secret places of detention and established a system of indefinite detention without trial. These policies were introduced insecrecy and beyond democratic control.

This collapse of human rights standards took place in countries regarded as stable democracies. It took several years before the political and judicial systems began to undothese mistakes – fear mongering and political bullying had paralyzed the normal corrective processes. It is absolutely important that lessons now are learned about what went wrong after Eleven September.

Even without such sad set-backs we know that human rights are never fully implemented. There are and will always be improvements to be made. One reason is that human rights enforcement relates to attitudes and that minimum requirements change with economic and social developments.

One consequenceis that the definition of government obligations for the implementation of human rights standards has developed considerably during the past fifty to sixty years. There is now a more heavy emphasis on the duty to ensure that the rights can be enjoyed by the individual – and by each individual. The horizon has moved forward.

The same goes of course for democracy. It is in its nature that democracy can never be absolute; in reality the discussion will have to be about degrees. This is no excuse for undemocratic tendencies, but an encouragement to further efforts, over and over again.

There will always be a need to work for the deepening of democratic procedures and attitudes. With every new generation it will be necessary to ensure that even the basic democratic values are understood.

Human Rights Education should therefore be given the highest possible priority.