06 March 2011

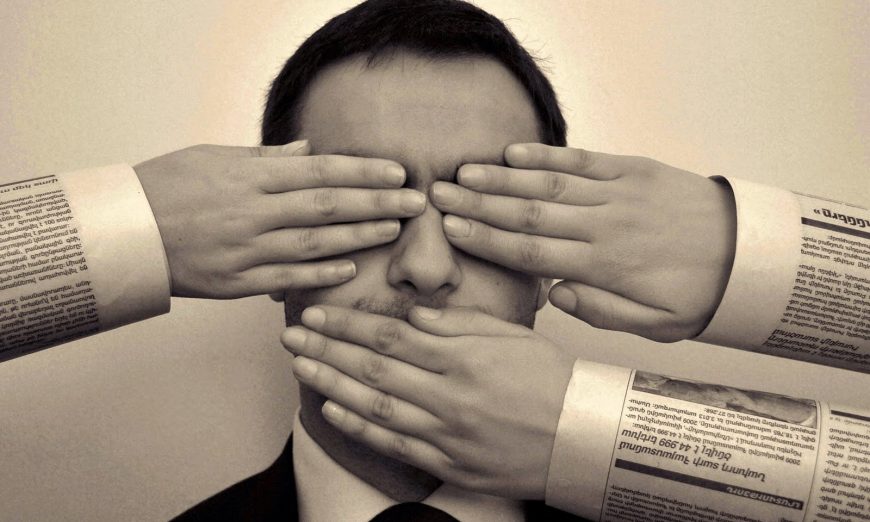

(Istanbul) – The arrest of nine journalists and writers on March 3, 2011, in the absence of clear reasonable cause, will have a chilling effect on free speech, Human Rights Watch said. The nine were accused of links to the alleged “Ergenekon” coup plots against the Turkish government.

Those arrested include Ahmet Şık and Nedim Şener, two prominent journalists known for critical reporting on the Turkish criminal justice system and police. Şık is co-author of a book about the investigations and trials in the Ergenekon case – after the alleged name given to their organization by the conspirators. He had been working on a book about the police. Şener had written a book on the murder of Hrant Dink, a renowned journalist and human rights defender, and its investigation.

“In the absence of evidence that the police have credible reason to think Ahmet Şık and Nedim Şener are responsible for wrongdoing, their arrests are a disturbing development,” said Emma Sinclair-Webb, Turkey researcher at Human Rights Watch. “It raises concerns that what is now under investigation is critical reporting rather than coup plots.”

On March 3, police searched the homes and workplaces of the nine journalists in Ankara and Istanbul, removing documents, computer hard drives, and CDs. The police detained all nine under an order from the Istanbul Heavy Penal Court No. 10, which authorized their police detention for questioning “on suspicion of being members of the Ergenekon terrorist organization and of spreading hatred and enmity among the population.”

Those arrested in Istanbul are: Şener, a Milliyet reporter; Şık, an independent journalist and lecturer at Bilgi University; Sait Çakır, a writer for the Oda TV channel; and Yalçın Küçük, a writer, who is already on trial for alleged connections with Ergenekon. Those arrested in Ankara are Doğan Yurdakul, an Oda TV coordinator; Mumtaz Idil, the Oda TV Ankara representative; Coşkun Musluk and Müyesser Yıldız, Oda TV writers; and İklim Bayraktar, an Oda TV reporter.

Police also searched the homes in Ankara of Aydın Bıyıklı, a police officer, and of Kaşif Kozinoğlu, a member of the National Intelligence Agency (MIT). Bıyıklı was detained. Kozinoğlu is reportedly currently serving abroad and was not detained.

Under Turkish law, the nine can be held in police custody for up to four days, after which they must either be released or brought before a prosecutor who would decide whether to charge them or release them without charge. If the prosecutor decides that there is evidence to bring charges, the prosecutor will issue an order for the person to appear before a court and rule on whether the person will be released or held pending trial.

In February, three other Oda TV journalists – Söner Yalçın, Barış Pehlivan and Barış Terkoğlu – were also detained, and on February 17 they were remanded to prison pending trial on charges including “membership of the Ergenekon terrorism organization.” Two other journalists, Mustafa Balbay and Tuncay Özkan, have spent two years and two-and-a-half years in prison respectively during their ongoing trial on charges of Ergenekon membership.

A secrecy order was issued by the prosecutor for the investigation into all the journalists, the police officer, and the intelligence agent detained over the last month, so the details of the full evidence on which the prosecutors are investigating them is not publicly available at this time. It is not yet clear whether those detained are under investigation for their legitimate activities relating to their professional duties as journalists and broadcasters or whether there is other evidence against them unrelated to their work as journalists. The charge of “spreading hatred and enmity among the population” is so broad and vague that it potentially could cover legitimate acts of journalism that are displeasing to the government.

In Şık’s case, the Turkish media recently reported that the manuscript of his latest book had been found in the offices of Oda TV, whose director was arrested and imprisoned for alleged Ergenekon links in February. Şık’s unpublished manuscript concerns alleged efforts at organization within the police force by a Turkish Muslim religious movement known by the name of its founder, Fethullah Gülen. Şık has publicly stated that he does not know how the TV channel obtained a copy of the manuscript.

Şık was the co-author with a Radikal daily newspaper journalist, Ertuğrul Mavioğlu, of a book about the Ergenekon investigations and trial, which described the scope of the case and raised concerns about it. As a result of writing that two-volume work, he and Mavioğlu are on trial and facing a possible prison sentence of four-and-a-half years. Like many other journalists in Turkey who have reported on the Ergenekon case, they were charged with “infringing the secrecy of an investigation.”

Şık was among the journalists working for the magazine Nokta, which in 2007 published the diaries of a former Naval Commander Özden Örnek that outlined the existence of coup plots. It was the publication of these diaries that first raised the possibility of alleged military coup plans against the government. The main Ergenekon investigation was opened soon after. A total of 273 people, including 116 military officers, have been charged in the Ergenekon trial with trying to overthrow the government and to instigate armed riots.

Şener has worked as a journalist for the daily Milliyet since 1994. Among his recent publications is a book on the Dink murder and the botched investigation and trial that followed. Şener was prosecuted following the publication of the book for a number of offenses under the Penal Code, including acquiring and publishing secret documents and publishing the name of a police officer. He was acquitted, but faces other ongoing trials in connection with the book. Like Şık, he has received a number of awards for his journalism.

The recent arrests are part of a wider pattern of prosecutions in Turkey against journalists who have reported on criminal investigations and trials such as the Ergenekon case and who have made statements critical of state authorities, state policies, the army, and politicians.

Human Rights Watch has repeatedly raised concerns about restrictions on freedom of expression and press freedom, through laws introduced by the Justice and Development Party government in the previous parliament. There are also serious concerns about the high number of prosecutions, some of which result in convictions, for statements that neither advocate nor incite violence.

Some journalists in Turkey have been subject to prolonged pre-trial detention. The more common trend is repeated prosecution, which Human Rights Watch considers a form of harassment and which can have a chilling effect on the legitimate right to free speech.

“The government should take steps to remove all restrictions in law on freedom of expression and to demonstrate a commitment to press freedom and lively critical debate, which together are the hallmarks of a democracy,” Sinclair-Webb said.

http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2011/03/04/turkey-journalists-arrests-chills-free-speech