I’ve lost a friend I’ll never be able to replace. I’ve lost a piece of my life. And now, for the first time, it occurs to me what torture it could be to live a very long life.

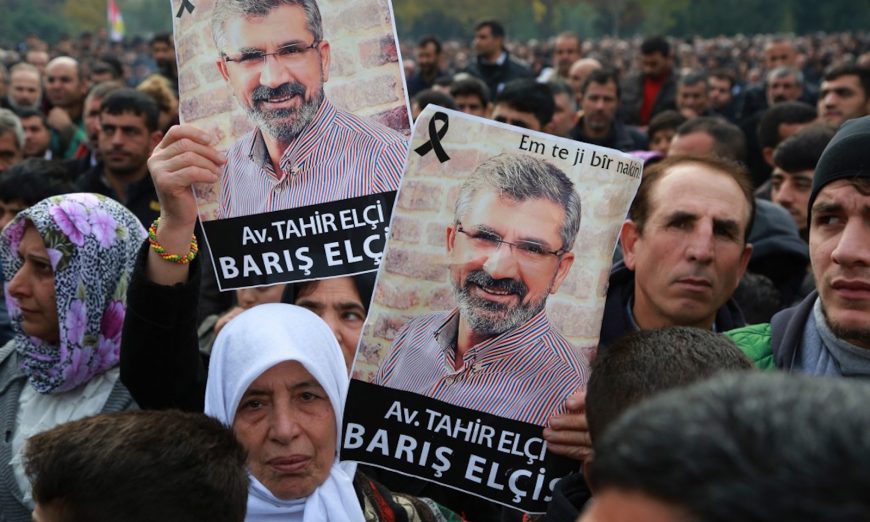

The death of a true friend is such a heavy weight. This is a very difficult column for me to write; I want to give Tahir his due, to describe who he really was, but it’s so difficult. On Sunday evening I told Tahir’s much-beloved wife Türkan, “When we tell people what sort of person Tahir was, they’re not going to believe us; they’re going to think we’re just saying these things because he’s dead now.”

The way he was killed has been compared to how Hrant Dink was murdered. And it really does resemble the Dink situation in many ways.

Just like Hrant, Tahir had his words picked apart by some; his lifelong stance and the values he fought for were all ignored and he was turned purposefully into an object of hatred. In his murder, as with Hrant’s, mechanisms for killing were in place. Both men were killed and both were completely abandoned and alone when it happened; in the wake of Tahir’s murder, as we saw with Hrant too, crocodile tears were shed by those partially responsible.

We live in a country that has lost its conscience. Both Hrant as well as Tahir were deserving of better; Turkey could handle neither of these men. Whatever Hrant was for Armenians, this is what Tahir was for Kurds. Both men represented the hope that their people could succeed in this country.

Tahir was a person who would never have been understood by those who killed him. A person with as big a heart as Tahir had could never be the champion of just one struggle, or a militant for any group.

A true envoy for peace

Just as you thought he was in pursuit of your “great cause,” you would turn and see Tahir standing strong with those whose wings were broken, those who were oppressed. And let’s hope that no one tries now to turn him into a figure for their own platform; you wouldn’t be able to do that unless you transformed him into some sort of caricature. His entire fight was simply about human rights. He was an envoy for peace.

I first met Tahir in 1998. Those were the days when Kurdish villages were being burnt down, when death was all too common in the streets of the Kurdish regions. Those were times when people were afraid to speak. At the time, there were a handful of Kurdish lawyers who had decided to bring some cases to the attention of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). I helped out in some of these cases, notably in the one focusing on the terrible human tragedies that occurred in the burning of the Kurdish village of Ormanici. Tony Fisher from England also helped on this case. In retrospect, that case was one of my life’s greatest traumas; as I learned from some of the friends I re-met at Tahir’s funeral, Tony had for years talked about this case everywhere he went.

It was one terrible winter day when the village of Ormanici, near Şırnak, had been burnt to the ground. The men of the village had been blindfolded and forced to walk kilometers through the snow and finally put into a windowless room somewhere. The room was so cold that they were actually stuck to the floor; others, whose feet were frozen, wound up getting gangrene and having their legs cut off. I’m only describing very little of what we head; we’re talking about horrors and cruelty difficult to believe.

Some of the villagers arrived at the hearing for this case, before the ECtHR, on crutches. One of these villagers was a 15-year-old boy. Those who remained in the village also had terrible things happen to them. A grenade was thrown, a young girl was hit, her intestines spilled out. Apparently the young girl was taken into the village mosque for protection and after living for a few days, ended up dying.

In any case, Tahir went and listened to all these stories and gathered them into one file. He brought all this material before the ECtHR. He was a great hero; I remember that as Tony and I nearly crumbled under the weight of what we were hearing, we were also caught under the spell created by Tahir. In the meantime, the seeds for a great friendship were planted between us. Tahir and I would meet up to speak of the things we had experienced at the trial, to talk about the lies we had listened to from government witnesses, to laugh, and later to cry.

In the end, though, this case which managed to traumatize me so profoundly was just one of hundreds that Tahir was involved in. We worked later on a case in which villagers were allegedly thrown from a helicopter. Tahir and I continued to laugh and cry together; Tony would ask us what we could possibly be laughing about. But we realized then that anyone from outside this insane asylum we call Turkey couldn’t possibly understand the tragicomedy of our lives and of these cases.

Later still, Tahir was to take on single-handedly one of Turkey’s most shocking cases to date, one involving a young man, 12-year-old Uğur Kaymaz, who was shot in the back 13 times. He became the voice for those victimized by JİTEM.

Taking Tahir to to the doctor

Tahir and I just kept on laughing at life through it all, even all the tragedy that surrounded us. Right now, Tahir’s death has managed to blur my sense of time, so I can’t recall when this happened, but there was a time when Tahir’s veins were blocked. I accompanied him to see a doctor in Ankara that we had been recommended. The doctor looked at the test results Tahir had brought in and said, “You could have a heart attack at any moment, you know.” And so there we were, suddenly hostages in the hospital. We couldn’t leave because of the risks to his health, but we also found it hilarious that we were stuck there. We laughed so hard tears came to our eyes.

Dear Tahir: I visited your home before your funeral took place. I took off my shoes before going in, but when I left your home, I accidentally put on one of my own shoes and one that belonged to someone else. I wore that mismatched pair of shoes throughout your entire funeral. I bet you would have laughed hard if you could have seen my feet.

I was so worried when you had to appear before a judge to receive sentencing on whether or not you’d go to prison. I was worried you’d have a heart attack in prison. Türkan had even prepared a bag filled with medicines for you. But now, I wish you’d been arrested and put in prison. If only you had stayed there, safe.

Your daughter Nazenin’s screams of anguish ripped through our hearts at the funeral. Maybe some thought this was simply the love of a daughter for her father. But most don’t even know what a good father you were. You had asked me if I would read a letter Nazenin had written when applying to a university abroad. I scolded Nazenin after I read her letter, telling her, “You want to be a lawyer, but in your letter, you didn’t even take one line to mention your father, who is such a great man of the law and such a champion of human rights.” Later, you called me and told me, “I wish you had spoken more supportively, Nazenin is very sensitive.” Of course, the screams I heard from Nazenin at your funeral reminded me how deep the love really ran.

Dear friend, you have left now, leaving behind you a gap that can never be filled. And with your death, there is a flood of rumors. I am not able to piece together everything I’m hearing now. Were you the victim of a planned assassination, or when a clash broke out, did someone say “Let’s grab this chance” and plant a bullet in the nape of your neck? At this point, I just don’t know; what I do know — and promise — is that I will do everything possible to understand the truth.

Tahir, losing a friend is such a painful thing. I feel like with your passing, I have lost a huge chunk of my life. I cannot even find the words to express my emotions. Nothing I say reflects my real feelings.

Farewell, dear friend. You were a voice for the voiceless, a figure who stood up for the invisible. I never ever knew anyone as compassionate as you in this life. I view my friendship with you as being one of the greatest privileges bestowed on me in this life. Farewell, dear Tahir.

Good bye, my friend.